onesteptwostep

Junior Hegelian

- Local time

- Today 9:45 AM

- Joined

- Dec 7, 2014

- Messages

- 4,253

What do you think matter is? Do you think they're things that actually exist and take up actual physical space, or do you think matter is something that's only a in a sense our perception of 'things' that 'are' and not physically existing?

What proofs of substance do you think can work?

Here are some of what past philosophers have said about substance::

Descartes: an entity which exists in such a way that it needs no other entity in order to exist, which to him meant a god of somesort. But to have things that actually exist from this substance, there needs to be an extension from this substance, which are mind and body, or physicality, thus his Cartesian dualism. To him, Descartes, substance existed and basically their extensions were an emanation from God.

Descartes: an entity which exists in such a way that it needs no other entity in order to exist, which to him meant a god of somesort. But to have things that actually exist from this substance, there needs to be an extension from this substance, which are mind and body, or physicality, thus his Cartesian dualism. To him, Descartes, substance existed and basically their extensions were an emanation from God.

Spinoza: Spinoza on the other hand didn't believe that there were extensions from God, but rather, that all things, both mind and body were of one substance, and that thus having one substance, which to Jewish philosopher meant also God, believed that all things were an outpouring of God, thus making him a pantheist. He's also a monist in the sense that substance consists of only one thing, contrasted with Descartes's dualism of the mental and physical. Spinoza however believed that there were an infinite number of attributes, or these extensions (as I understand Spinoza).

Spinoza: Spinoza on the other hand didn't believe that there were extensions from God, but rather, that all things, both mind and body were of one substance, and that thus having one substance, which to Jewish philosopher meant also God, believed that all things were an outpouring of God, thus making him a pantheist. He's also a monist in the sense that substance consists of only one thing, contrasted with Descartes's dualism of the mental and physical. Spinoza however believed that there were an infinite number of attributes, or these extensions (as I understand Spinoza).

Leibniz: Also another monist, believed that all things were created by something called Monads. He believed that there were an infinite number of substances and that God was transcendent over these Monads, and that God had ordained a pre-established harmony for the workings of these Monads, meaning that even if they didn't have any connection with each other in a sort of a deterministic, natural law way, they were pre-established by God to work together. In a sense Leibniz was a deterministic, though he believed freedom was just us going along with the flow of the pre-established order, thus in a cognitive dissonance way he thought true freedom was going along with God's plans.

Leibniz: Also another monist, believed that all things were created by something called Monads. He believed that there were an infinite number of substances and that God was transcendent over these Monads, and that God had ordained a pre-established harmony for the workings of these Monads, meaning that even if they didn't have any connection with each other in a sort of a deterministic, natural law way, they were pre-established by God to work together. In a sense Leibniz was a deterministic, though he believed freedom was just us going along with the flow of the pre-established order, thus in a cognitive dissonance way he thought true freedom was going along with God's plans.

Berkeley: Also believed that substances existed, but only as spiritual things, as we have no way of knowing where actual things existed or not, because the material cannot prove whether the material exists, because to prove material exists one needs something supernatural, or beyond the natural, to prove the system of the natural, just as you need something that's not water to prove what water is. Berkeley however is not a monist like Spinoza, but believed that there was an mental and spiritual split/dualism.

Berkeley: Also believed that substances existed, but only as spiritual things, as we have no way of knowing where actual things existed or not, because the material cannot prove whether the material exists, because to prove material exists one needs something supernatural, or beyond the natural, to prove the system of the natural, just as you need something that's not water to prove what water is. Berkeley however is not a monist like Spinoza, but believed that there was an mental and spiritual split/dualism.

Those who believed substances don't exist at all: Hume, who thought that since they cannot be proved by the senses/impressions, cannot exist. According to wiki Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault and Deleuze also didn't believe in substances because they believed that they were leftovers of Platonic idealism.

Those who believed substances don't exist at all: Hume, who thought that since they cannot be proved by the senses/impressions, cannot exist. According to wiki Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault and Deleuze also didn't believe in substances because they believed that they were leftovers of Platonic idealism.

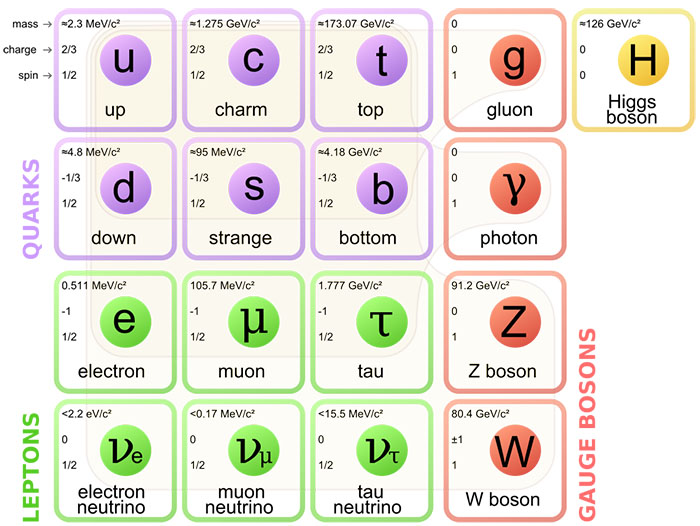

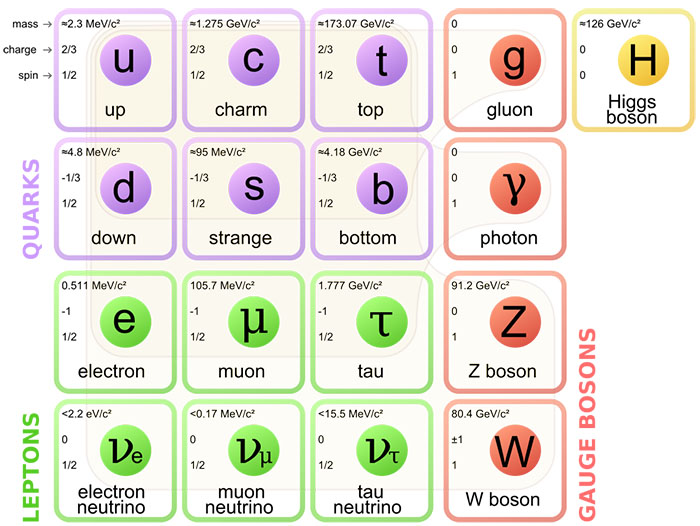

For me personally, I think substances do have to exist because science up to now has been splitting the atom in an indefinite fashion (the thing which isn't supposed to be able to be split, in the Greek sense of the word). If we were to split the atom at the moment we would have protons, elections and neutrons, but when we smash protons together we get the matter that's found in the Standard Model. Here we have quarks and leptons and bosons- but my question is this: if we had an infinite amount of energy to smash even the smallest of these subatomic elements together, wouldn't we be left with even smaller subatomic particles? Thus, my reasoning is that with enough energy there would have to be a split of these 'elements' to the infinith degrees, making it theoretically impossible to find 'the particle' which constitutes all matter. Thus, if you're following my logic, there would be some rationale in believing that there's a substance that exists which is not in a sense physical but something that's non-physical, like the spiritual or the mental, not just the physical.

For me personally, I think substances do have to exist because science up to now has been splitting the atom in an indefinite fashion (the thing which isn't supposed to be able to be split, in the Greek sense of the word). If we were to split the atom at the moment we would have protons, elections and neutrons, but when we smash protons together we get the matter that's found in the Standard Model. Here we have quarks and leptons and bosons- but my question is this: if we had an infinite amount of energy to smash even the smallest of these subatomic elements together, wouldn't we be left with even smaller subatomic particles? Thus, my reasoning is that with enough energy there would have to be a split of these 'elements' to the infinith degrees, making it theoretically impossible to find 'the particle' which constitutes all matter. Thus, if you're following my logic, there would be some rationale in believing that there's a substance that exists which is not in a sense physical but something that's non-physical, like the spiritual or the mental, not just the physical.

What do you think? I've searched on youtube for good videos on substances but I've found none so far, so sorry if this doesn't really make sense. I'll try my best to clarify things if anyone has questions.

What proofs of substance do you think can work?

Here are some of what past philosophers have said about substance::

What do you think? I've searched on youtube for good videos on substances but I've found none so far, so sorry if this doesn't really make sense. I'll try my best to clarify things if anyone has questions.